It would seem to be a simple matter of conscience that no child should ever stand before a judge without having an attorney as an advocate. Younger children in particular may not even understand the significance of their day in court or how a judge’s ruling can profoundly impact the rest of their lives. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of children who have fled gang violence and grinding poverty in Central American nations, and for whom a deportation order issued by a U.S. immigration judge could mean the difference between life and death. Unfortunately, U.S. policies regarding “unaccompanied minors” are not governed by conscience.

As a story in Politico discusses in detail, “child migrants from Central America are still paying a heavy price for President Barack Obama’s decision last summer to rush them into deportation proceedings without first taking steps to provide legal counsel.” According to Politico’s analysis of numbers from the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), among cases completed since July 18, 2014, “barely half the children had legal representation.” And while “the picture has improved over time,” the fact remains that:

“in 38 percent of the cases completed since last Christmas, the child was still without counsel. Even since mid-April, there have been an average of 100 case completions per week in which there is no record of a defense attorney.”

The story notes that “this picture is skewed by the stubbornly high level of deportation orders issued by judges ‘in absentia,’ when the child defendant does not appear in court.” However, “migrant rights attorneys argue that this is a Catch-22 situation — attorneys help ensure that children appear in court and have a full opportunity to pursue their claims.

Regardless of the courtroom scenario, the underlying problem is that deportation orders are being issued for children who have not had the benefit of legal representation, and who will or would be returning to situations that put their lives in danger. Research conducted by Elizabeth Kennedy has found that:

“crime, gang threats, or violence appear to be the strongest determinants for children’s decision to emigrate. When asked why they left their home, 59 percent of Salvadoran boys and 61 percent of Salvadoran girls list one of those factors as a reason for their emigration.”

For these children, and their parents, the decision to embark upon a clandestine and potentially fatal journey northward, through Mexico and into the United States, is not taken lightly. It is a last resort to save the children from being murdered or forced to join a gang. Not surprisingly, many of these children qualify for protection under international law. In fact, a survey by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) found that 72 percent of the children from El Salvador, 57 percent from Honduras, and 38 percent from Guatemala could merit protection.

However, the overwhelming response of the U.S. government to this humanitarian crisis has been deterrence, not protection. Fast-paced “rocket dockets” have been established that quickly dispatch the cases of unaccompanied children—to send the message that other Central American families shouldn’t also try to send their endangered children to the United States. Meanwhile, under U.S. pressure, Mexico has heightened its migrant interdiction efforts along its southern border with Central America, thereby saving the Border Patrol and immigration courts a lot of trouble.

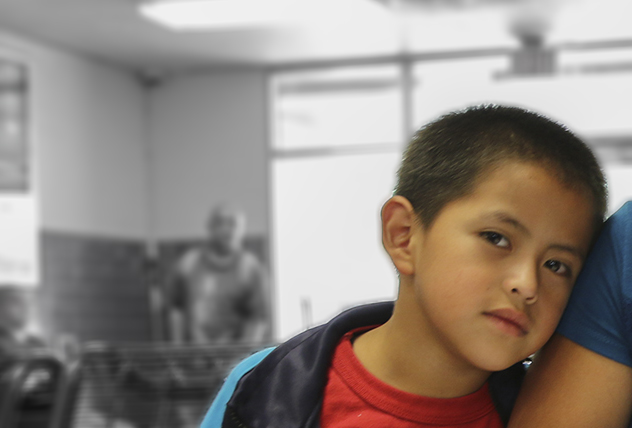

All too frequently lost in the shuffle are the children themselves—many of whom are, for all intents and purposes, refugees fleeing violence.

Photo by uscc4all.

FILED UNDER: Children, Executive Office for Immigration Review, featured, unaccompanied children, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees