When the Biden administration launched new Family Reunification Parole programs earlier this year, it pointed to existing programs for Cuban and Haitian families as the model. The new programs would allow some people from Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras stuck in the immigrant visa backlog to join their family members in the United while waiting for their visas to become available.

But the spotty and limited implementation of the original 2007 Cuban Family Reunification Parole (CFRP) and 2014 Haitian Family Reunification Parole (HFRP) programs—which no new families had been invited to apply for since 2016—raised concerns about the potential efficacy of these programs.

Now, though, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has announced that it’s revamping the CFRP and HFRP to be more in line with the new programs. The new process will take place almost entirely online and eliminate a requirement for an additional in-person interview at a U.S. consulate in Havana or Port-au-Prince. The changes point to a renewed commitment to the programs—and raise hopes that the administration is putting real resources behind family reunification parole.

The family reunification parole programs are limited to people who have already been approved to settle in the United States, as relatives of U.S. citizens or green card holders. While waiting for immigrant visas to become available—a process that can take years due to limited quantities—individuals may now be allowed to live and work legally in the U.S. on a temporary, discretionary grant of parole. However, the federal government must invite a family to apply for a parole grant—meaning that the number of people who can benefit is dependent on the resources the government chooses to put into issuing invitations and processing applications.

As DHS points out in Federal Register notices about each program, the U.S. government’s capacity to conduct interviews in Cuba and Haiti has been severely limited. The embassy in Port-au-Prince has been closed since 2019. The Havana embassy, which restarted consular services in January of this year after being closed in 2018, is still getting back up to speed. At the same time, conditions in both countries are extremely bad, making it more difficult for people to get to the embassy in Havana for interviews. This in turn makes it all the more urgent for would-be beneficiaries in both countries to get their family members to safety in the United States.

By eliminating the in-person interview requirements, the Biden administration has removed the biggest obstacle to reinvigorating the Cuban and Haitian programs. And by ensuring that all six family reunification parole programs operate in the same way, it’s making it easier to scale up all of them at once.

Indeed, reports from lawyers indicate that people from Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are already receiving invitations to apply for the new parole programs.

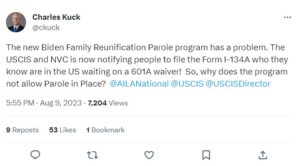

But those reports also indicate there’s a problem with the way the government is issuing invitations—raising an obvious blind spot for the programs as a whole.

Charles Kuck, an immigration attorney, is referring to people who have been approved for an immigrant visa while living in the U.S. without authorization. They are waiting for the government to okay a waiver form so that they can continue with the process of receiving a green card.

To unpack this: People who are living in the U.S. without authorization, but who are eligible relatives of U.S. citizens or green card holders, can receive immigrant visas through a petition filed by their relatives. However, federal law bars many people who have lived in the U.S. illegally from obtaining green cards for three or 10 years (depending on how long they’ve been unauthorized), but only if the person leaves the country. But because the visa application process generally requires an interview overseas, undocumented applicants face the risky proposition that they might not be allowed to enter the U.S. again. The solution to this is a “provisional” waiver of this bar (the I-601A form) which can be approved before the person has to leave the U.S. and travel to a consulate to complete the visa process.

By definition, I-601A applicants are people the federal government already knows are in the United States – it has forms on file that it needs to approve in order for them to safely and temporarily leave. By not checking its list of potential family reunification parole invitees against the list of people who have applied for family visas while in the U.S., the government has limited the potential benefit of the program.

As Kuck and others have pointed out, the Biden administration could actually use family reunification parole programs to help these families too. If it granted “Parole-in-Place,” it would allow beneficiaries to avoid the three- and 10-year bars and move forward with their applications – bringing them closer to green cards.

As the government’s changes to the Cuban and Haitian programs show, it sees the family reunification parole programs as a way to bring more people into the U.S. legally while they’re stuck in visa limbo. But with Parole-in-Place, it could help some families get themselves unstuck from a different bureaucratic limbo – the wait for their waivers to be approved—and move them toward the date when their long-awaited green cards finally arrive.

FILED UNDER: Cuba, Department of Homeland Security, Haiti