On Thursday, a Texas federal judge will hear 25 states’ arguments to block President Obama’s recent immigration executive actions. But the suit has more value as political theater than as a legitimate constitutional challenge. There’s no merit to the case. The president, cast by states as the villain, acted entirely within the bounds of his constitutional authority, and the plaintiffs do not even have standing to be in federal court.

The president’s actions included a directive to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to consider two categories of immigrants for deferred action: the parents of U.S. citizens or Lawful Permanent Residents who have lived here five years without serious incident and, expanding upon a 2012 directive, immigrants who came here as children and have already lived here several years without serious incident.

Twenty-five states, led by Texas and primarily in the South, responded by suing the administration. Conspicuously, out of those 25 states, plaintiffs filed the case in Brownsville, Texas, where the only active federal judge has repeatedly and loudly criticized Obama administration immigration policy.

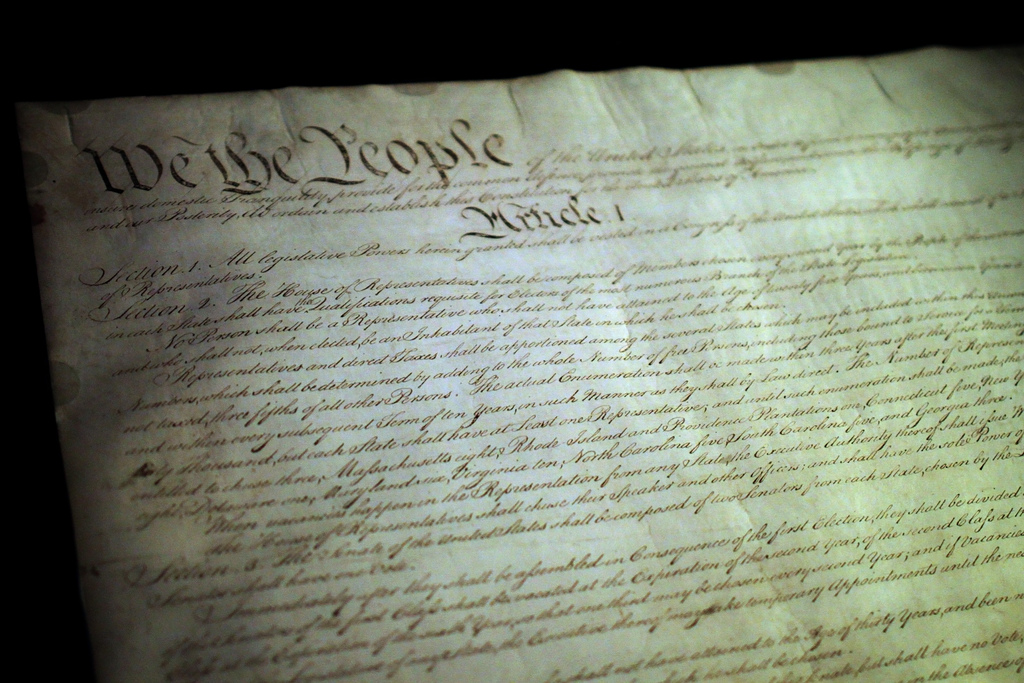

Substantively, the states who are plaintiffs complain that the president is not “executing” the law as the Constitution provides. But in immigration law, Congress has expressly granted the executive branch very broad discretion in pursuing removal actions, and specifically in setting policies and priorities for those actions. The enabling statute could not be more specific: Congress expressly confers on the DHS secretary the authority for “[e]stablishing national immigration enforcement policies and priorities” (emphasis added). And as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Jackson wrote in 1952, “[w]hen the President acts pursuant to an express or implied authorization of Congress, his authority is at its maximum, for it includes all that he possesses in his own right plus all that Congress can delegate.” President Obama’s directive chose to drop two categories of people to the bottom of the enforcement pile, and even then, for only a two or three-year period, assuming a later president or Congress does not act.

The plaintiff states may not like the priorities set or the law empowering the president and DHS to set them. But their remedy is to turn to Congress because the president acted well within the bounds of executive power. In light of the express congressional authorization to set “enforcement policies and priorities,” the president and DHS officials have executed the law exactly as directed.

Further, Congress’ long pattern of acquiescence would alone be enough to validate the President’s action. In the last 35 years, at least three other presidents—Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush—have similarly announced deferred actions, on at least five different occasions. One George H.W. Bush directive potentially affected up to 1.5 million people. Plainly, these presidents concluded as President Obama did that setting enforcement priorities was well within presidential power. And throughout this time, Congress took no action to object to, remove or modify the president’s discretion. Under separation of powers law, that acquiescence now forecloses any suggestion that President Obama has overstepped his power.

Of course, the states bringing this lawsuit have larger obstacles before even addressing the merits. They do not have “standing” to proceed in federal court. Standing requires an injury, and the states claimed injury is the increased law enforcement supposedly made necessary because the president’s directives have caused more people to cross the border. This theory, however, blames the president for this summer’s influx of Central Americans on an extremely speculative theory of “chain of causation.” At one point, plaintiffs lay at the president’s feet all upcoming increases in immigration. On another page, plaintiffs acknowledge substantial increases that predated the president’s directive. Most noticeably, the plaintiffs completely ignore the recent political turmoil and violence in Central America that motivated high numbers of arrivals.

Likewise, the plaintiffs cannot show the “redressability” necessary for standing, which requires that the plaintiffs’ requested relief be able to repair their alleged injury. Even assuming the court struck down the president’s directive, all that would happen is that the implementation of the deferred action programs might be delayed in certain parts of the country. Other immigrants will keep coming to escape violence and lack of opportunity just as they were the day before the judge’s ruling, and states will be affected—or not—as they are now.

In sum, there has been no abdication of duty by the president, no usurpation of power and no “amnesty” granted, as many would like to alarm people into believing. So it might be best to drop the lawsuit and start working on Congress to effect permanent immigration reform.

Photo by Mr. T.

FILED UNDER: executive action, featured, Immigration Law