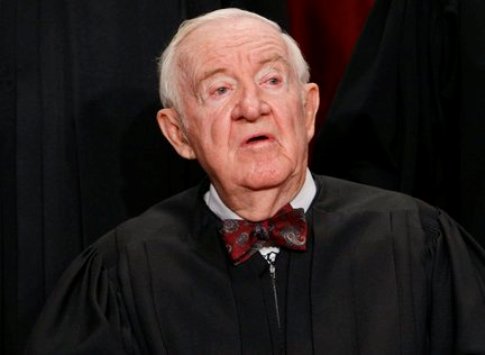

Retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, author of the Padilla v. Kentucky opinion.

Retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, author of the Padilla v. Kentucky opinion.

Immigrant advocates rejoiced last spring when the Supreme Court made clear in Padilla v. Kentucky that criminal defense lawyers must inform noncitizen clients if pleading guilty to a particular crime could result in their deportation. Since then, the Court’s ruling has provided much-needed relief for many immigrants whose lawyers failed to properly advise them. At the same time, however, the immigrants’ rights community is realizing that the decision has its limits and will not help all noncitizens whose lawyers failed to give such advice in the past.

The latest reminder came earlier this month, when the Virginia Supreme Court unanimously ruled that trial judges could not modify old sentences—even by one day—to spare previously convicted immigrants from deportation. Similarly, the Illinois Supreme Court last November rejected as untimely the claim of a longtime permanent resident whose lawyer incorrectly stated in open court that the agreed-upon plea bargain would carry no immigration consequences.

What gives? While seeming to violate Padilla v. Kentucky, these recent decisions reveal a frustrating reality of our legal system. In many states, criminal defendants face numerous obstacles to even filing challenges to their original convictions or guilty pleas, such as strict time limits and requirements that they remain in physical custody—a problem further compounded by court decisions which narrowly interpret laws meant to enable defendants to reopen their cases in compelling circumstances.

But despite the ruling of the Virginia court, Padilla v. Kentucky remains a significant decision. For one thing, it recognized the harshness of deporting long-time permanent residents and the importance of providing sound advice to noncitizens facing criminal charges. For another, immigrants can still rely on the ruling if their original appeals remain ongoing, if they have time to file a federal habeas corpus petition, or if they were convicted in states more willing to provide remedies for reliance on bad legal advice.

But the ruling’s greatest impact lies not in the relief it may offer to immigrants who were misadvised in the past, but in how it will shape the plea bargain process for noncitizen defendants in the future. Why? Unlike ICE attorneys, who are generally unwilling to negotiate, local prosecutors reach plea agreements in the vast majority of cases, if only to avoid the time and expense of proceeding to trial.

As (now retired) Justice John Paul Stevens, who authored Padilla v. Kentucky, subtly put it, “[b]y bringing deportation consequences into this process, the defense and prosecution may well be able to reach agreements that better satisfy the interests of both parties.” Put more bluntly: criminal defense lawyers won’t unwittingly accept plea bargains that result in harsh immigration consequences, and local prosecutors will have to offer more favorable deals unless they want to go to trial.

Of course, this calculus won’t apply to immigrants charged with crimes carrying serious prison sentences. But as Justice Stevens noted, where immigrants face some charges that mandate deportation and others that do not, they can plead guilty to the latter in exchange for the dismissal of the former. And where future deportation depends on the length of the sentence, no prosecutor would go to trial to obtain a year-long sentence when the defendant is willing to serve up to 364 days.

The recent decisions in Virginia and Illinois may still be appealed. But even if the rulings stand, Padilla v. Kentucky will be far from a dead letter. For untold numbers of future immigrant defendants, its impact on the plea bargain process will result in better legal advice, more appropriate sentences, and less need to revisit old cases in the first place.

Photo by Bob Higgins.