Here are the messages that the 350,000 Venezuelans in the U.S. who were granted Temporary Protected Status in 2023 have heard from the federal government since January:

January 17: You can keep your TPS protections until fall 2026.

January 28: We’re reviewing whether you can keep your TPS protections.

February 5: Your TPS protections will expire on April 7, 2025.

March 31: Your TPS protections can remain valid while a lawsuit about them is pending.

May 19: Your TPS protections have already been revoked. Probably. We assume.

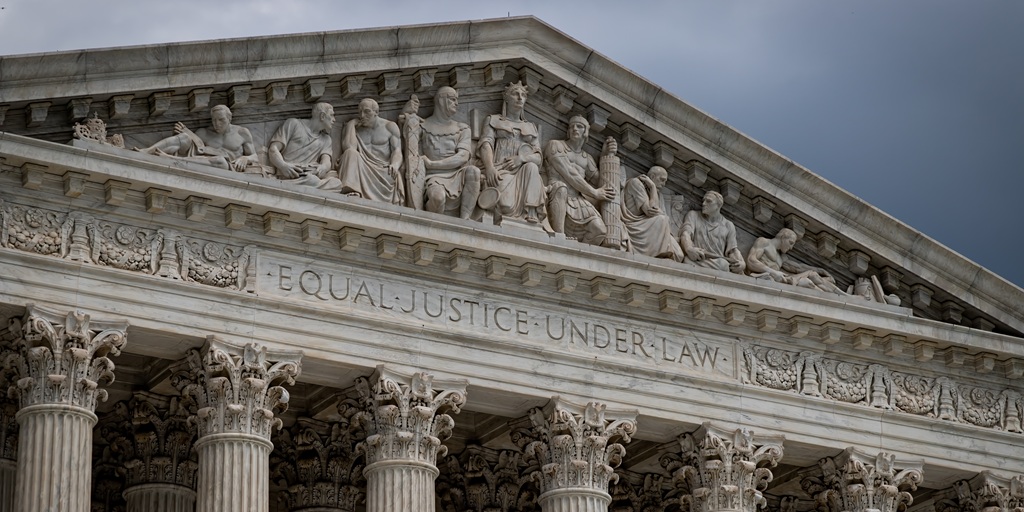

With that last one – a single-page unsigned order, which, technically speaking, overruled an order to postpone the Department of Homeland Security’s termination of TPS for Venezuela – the Supreme Court achieved what law professors believe to be the biggest instantaneous “de-documentation” of immigrants in U.S. history. 350,000 people who woke up on Monday with legal status in the U.S. went to bed Monday without it.

Probably. We assume.

The lack of clarity is maddening. But it’s, in a way, the logical endpoint of the way TPS holders have always had to live their lives – 18 months at a time – and of the Trump administration’s insistence on pulling the rug out from under people who had filed their papers with the U.S. in exchange for permission to stay.

The Supreme Court’s Legal Triple Negative

Going into the procedural details of how all of this happened will not exactly make the constant flip-flops any less confusing, but here goes:

In 2023, President Biden decided that conditions in Venezuela were bad enough that it would be inappropriate to deport anyone there, and therefore Venezuelans in the United States needed Temporary Protected Status (if they lacked other legal status) to remain here legally until conditions improved. He both extended TPS for Venezuela – allowing people who had received TPS after it was first offered in 2021 to renew it for an additional 18 months, which would be added to the end of their existing TPS period – and redesignated it, allowing Venezuelans who had arrived since 2021 to apply for TPS for the first time and receive 18 months of protections.

As many as 350,000 people took the government up on the offer, receiving protections through April 2025. Many of them – about 67,000 – had arrived in the United States with a different form of temporary protection: they were paroled in under the Biden administration’s “CHNV” (Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan) program, with protections that expired after two years. Applying for TPS allowed someone whose parole was set to expire in January 2025, for example, to give themselves an extra few months, a more durable form of protection, and the potential for further extensions if the executive branch chose to give them.

A few days before leaving office, the Biden administration published a notice that essentially combined the 2021 and 2023 TPS timelines, and allowed both to reapply for TPS through September 2026. The Trump administration seized on this move, and moved within days of its inauguration to vacate Biden’s decision; a few days later, it issued its own proclamation, saying it would be ending TPS for the 2023-protected Venezuelans after all, and they would lose their legal status on April 7.

TPS holders sued the administration over the bait-and-switch. In an order issued mere weeks before the expiration date, a federal judge ordered DHS to “postpone the effective date” of its decision to end TPS for Venezuela, while the lawsuit over the legality of the decision was ongoing.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the postponement. The Supreme Court, on Monday, overturned it.

So if the termination of TPS would have gone into effect already, but it was postponed, and now it’s been unpostponed, that means it’s implicitly already in effect…right?

Here’s the problem: the Supreme Court didn’t actually clarify whether the termination is in effect now, or whether the government has to do something to make the original April 7 termination effective. Litigators in the case say that it’s up to the government to make the next move, and announce how it is interpreting the court’s order – which is to say, whether it considers all 350,000 Venezuelans to be already out of status and potentially subject to removal, or whether it’s going to set a new date by which they will become so. (The litigators aren’t saying that whatever the government does will be legally correct, just that they have to take the initiative.)

As of Tuesday evening, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services webpage about TPS for Venezuela had not been updated to reflect Monday’s ruling. It still said that work permits issued to 2023 TPS holders would be auto-extended through next April – “under protest pursuant to court order.”

Leaving TPS Holders To Gamble with Their Freedom

TPS holders are already in a “liminal status” that they can never convert to permanent residency, and every expiration date brings with it the possibility that the president won’t grant another extension – underlined during Trump’s first term when he tried to do just that for hundreds of thousands of people from Haiti, El Salvador, and others. Those terminations were held up in court until President Biden took office and undid them.

Telling people they would be able to plan for another 18 months of life in the United States, then telling them they had just over 60 days to leave, is a different category of arbitrariness. (Technically, the Supreme Court acknowledged, people who had already applied for and received new TPS grants between January 17 and February 5 might legally be allowed to keep them – but given the processing time for TPS applications, it is highly unlikely any such people exist.) The cruelty is especially apparent given that, in the weeks before the April 7 expiration date, TPS holders in the US saw their compatriots deported without hearings and sent to a notorious Salvadoran prison under the Alien Enemies Act — including at least four people with active TPS.

The threat of detention and deportation was terrifying. The court ruling postponing the termination offered little psychological relief to Venezuelan TPS holders. One Venezuelan advocate described her state of mind this way to Politico in the days following the reprieve: “It’s exhausting, it’s disheartening, it’s painful and I’m not going to lie, last night I cried.”

The Supreme Court’s order shows why they were uncomforted. What courts grant, courts can take away. Probably. We assume.

Add to this the fact that some Venezuelans who have TPS may also still be within the two-year window for their CHNV parole to be valid – except that the Trump administration is trying to kill that, too. That termination has also been held up in court (for now), but the Trump administration is asking the Supreme Court to overturn that ruling, too. A decision could come any day.

The lack of clarity on the question of whether TPS has already been terminated has enormous real-world stakes. Should someone with TPS show up to work their next shift, on a work permit that was valid on Monday morning but may now be (in legal terms) six weeks past its expiration date? Should they cancel their leases and buy plane tickets, or keep studying for their final exams at school? If they are arrested, will the ICE agents accept the explanation that no one appears to know if they have valid papers or not?

The strategy of this administration is to cast as broad a net of enforcement as possible – and to make it clear even to those who aren’t caught up in it today that they could be caught up in it tomorrow. But the rule of law is built on certainty and predictability. A legal regime under which people can have their status taken away from them in a day, without even a clear explanation that that’s happened, fully undermines both of those. A law that can’t be relied on isn’t a law anyone can live by.

FILED UNDER: Supreme Court