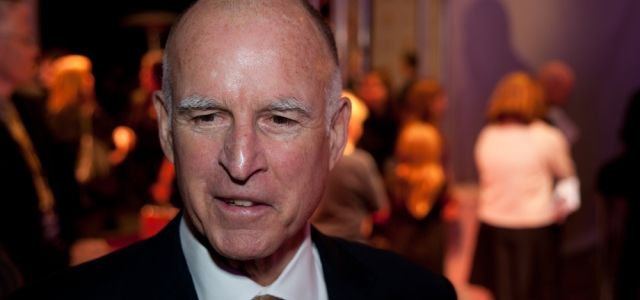

On the same day thousands of immigrant activists rallied across the country for immigration reform, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed several bills into law that put the state at the forefront of the efforts to fix immigration policies at the state and local level. Among the measures Brown approved was the TRUST Act, which limits who state and local police can hold for possible deportation. “While Washington waffles on immigration, California’s forging ahead,” Brown said in a statement. “I’m not waiting.”

On the same day thousands of immigrant activists rallied across the country for immigration reform, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed several bills into law that put the state at the forefront of the efforts to fix immigration policies at the state and local level. Among the measures Brown approved was the TRUST Act, which limits who state and local police can hold for possible deportation. “While Washington waffles on immigration, California’s forging ahead,” Brown said in a statement. “I’m not waiting.”

This year’s bill was the third version of the TRUST act to be considered by the California legislature. Brown vetoed the bill in 2012, so Assemblyman Tom Ammiano, who sponsored the bill, changed it to address the concerns from Brown and some law enforcement officials. Under the new law, “immigrants in this country illegally would have to be charged with or convicted of a serious offense to be eligible for a 48-hour hold and transfer to U.S. immigration authorities for possible deportation,” according to the Los Angeles Times. The law will go into effect January 1, 2014.

The TRUST Act was just one of eight immigration reform measures Brown signed on Saturday. Among those were bills that will allow undocumented immigrants to be licensed as lawyers. In early September, the California Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case about if an undocumented immigrant may receive a license to practice law in California and has not yet issued its ruling. Two other new laws also make it a crime for employers to “induce fear” by threatening to report a person’s immigration status and allow for the suspension or revocation of employers’ business licenses if they retaliate against employees because of citizenship or immigration status.

The slew of new laws follows the state’s Domestic Worker’s Bill of Rights law, which Brown approved in September. And on Thursday, Brown also signed a new policy to allow people to apply for driver’s licenses regardless of immigration status. “This is only the first step. When a million people without their documents drive legally with respect to the state of California, the rest of this country will have to stand up and take notice,” Brown said when he signed the law. State officials are working to develop the guidelines of eligibility for the licenses, which will have different marks to distinguish them from other driver’s licenses, and probably won’t issue any until late 2014 or early 2015.

California is not the first state to enact many of these reforms. For example, 10 other states have laws allowing undocumented immigrants to qualify for driver’s licenses—seven of which were approved this year. New Mexico has granted more than 90,000 licenses to foreign nationals since 2003. And in the eight years that Utah has processed driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants, activists say about 75 to 80 percent of immigrants who were eligible ended up applying. And earlier this year, Connecticut legislators unanimously passed a version of the TRUST Act to limit when law enforcement agencies in the state could hold people at the request of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

As an editorial in The New York Times explains, “The states cannot fix the whole system, of course, or legalize anybody. But they can try to address issues and prod Washington by example.” While other states may have passed some measures before California, the scope and impact of these bills will be dramatic, as 2.5 million, or roughly one-fifth, of all undocumented immigrants in the U.S. call California home.

Photo Courtesy of Randy Miramontez / Shutterstock.com

FILED UNDER: California, Executive Branch, immigration detainers, Jerry Brown, trust act, undocumented immigration