In a decision issued Friday, a district court in California ruled yet again that the government is violating a long-standing settlement agreement protecting the rights of children in immigration detention. Advocates for immigrant children went to court in February to argue that the government’s family detention centers violate the Flores v. Reno settlement agreement, which set minimum standards for the detention, release and treatment of children subject to immigration detention. In late July, the district court agreed, finding that the government’s current family detention policy fails to meet these clear standards. The latest ruling, which came after the government received yet another chance to justify its widespread detention of asylum-seeking women and children to the court, reaffirmed that children should generally be released from family detention centers within five days. The government must put this ruling into effect by October 23, 2015.

The court’s decisions lay out a path forward for the treatment of immigrant families fleeing violence. Under the Flores settlement, children should be released from detention as quickly as possible—and despite the government’s repeated attempts to narrow Flores’ scope, this is true both for children arriving in the United States unaccompanied and those with their families. Preferably, a child should be released to one of his parents, even if the parent was taken into immigration detention with the child. While the court noted that there could be an exception in the event of emergencies or influxes, children generally should not remain in unlicensed, secure family detention centers for longer than five days. The court castigated government officials for “unnecessarily dragging their feet” in releasing immigrant children from detention.

The order also made clear that the government’s policy of detaining immigrant families in violation of the Flores settlement had not materially changed since its last order on July 24 and that further delay in compliance with the court’s orders was inappropriate. According to the court, any suggestion that compliance with the order would lead to increased migration of Central American families was “speculative at best, and, at worse, fear mongering”—which echoes another district court decision that found detaining families to deter future migration was based on “particularly insubstantial,” and likely unconstitutional, justifications.

It remains to be seen how the government will react to the clear decisions in the Flores case. The appropriate response is unambiguous: the government should take immediate steps to release families currently in immigration detention, safely and with clear information about their ongoing immigration cases. In the future, families seeking refuge in the United States should receive a fair opportunity to present their cases to an immigration court—without being locked away in unlicensed and inhumane detention centers. But given the government’s history of delay, families must wait to see whether the government will now comply with the court’s order and end widespread, lengthy detention of immigrant women and children.

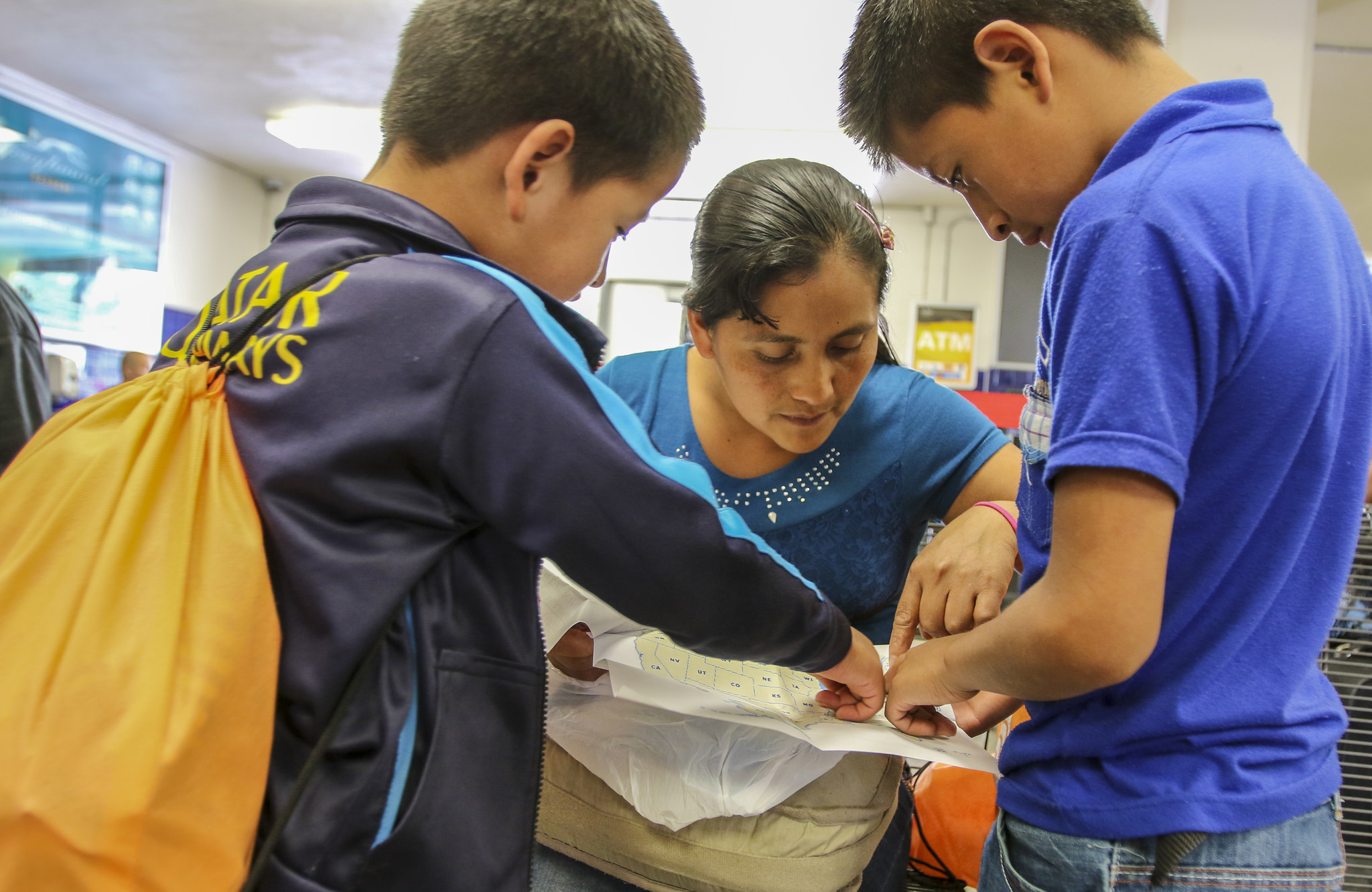

Photo by uusc4all.

FILED UNDER: Family Detention, featured, Flores v. Reno