The state of Alabama settled a lawsuit last week over one of the last remaining provisions of HB 56, the punitive immigration measure often called the “show me your papers” law. Legislators first approved the law in 2011, but when lawmakers passed revisions to HB 56 in 2012, they including a requirement that the state “publish online the names of immigrants who are detained by law enforcement, who appear in court for any violation of state law, and who unable to prove they are not “unlawfully present aliens,” according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). State officials agreed on Thursday to end the “scarlet letter” provision of the law. “What you have now is the state of Alabama coming to terms with the fact that not only was this law bad policy, it was also illegal as a constitutional matter,” said Karen Tumlin, managing attorney for the National Immigration Law Center, according to BuzzFeed News.

The “scarlet letter” provision was the last provision of Alabama’s anti-immigrant law challenged in court. Civil rights groups—including SPLC, the ACLU, the National Immigration Law Center, and the ACLU of Alabama—filed a lawsuit against the list requirement on behalf of four undocumented immigrants who were arrested for allegedly fishing without a license, which is a misdemeanor offense in Alabama. They would have been placed on the state’s list of immigrants without legal status because they could not prove they were “lawfully present aliens” in state court.

The settlement agreement, which is awaiting the approval of a federal judge, “requires the state to institute a policy that bars the publication of any list naming people allegedly “unlawfully present” in Alabama,” according to SPLC, and requires any immigration information the state collects through the Administrative Office of the Courts to be kept confidential.

This settlement over the “scarlet letter” provision is the latest step in the steady unraveling of Alabama’s extreme law that attempted to, as one of the law’s sponsors put it, “make it difficult for them to live here so they will deport themselves.” Alabama already settled most of the lawsuits brought by the Justice Department and civil rights groups against HB 56 in October 2013 after the Supreme Court refused to hear the state’s appeal of a previous federal court’s ruling that gutted the law. Sam Brooke, an attorney for the SPLC, said one of those rulings ending the law’s criminalization of renting property to undocumented immigrants “was fundamental in saying that there likely was racial animus behind the passage of this law.”

According to BuzzFeed News, the quiet death of HB 56 shows a turn against anti-immigrant state legislation:

The law’s opponents say this is because HB 56 proved to be little more than a headache and an embarrassment to Alabama. And even as the House of Representatives is pursuing similarly harsh anti-immigrant bills on the federal level (such as the SAFE act), they also tie the decline of HB 56 to a broader turn away from anti-immigrant legislation around the country on the state and local level. […]

“It’s telling that you’re not seeing new proposals that target immigrants coming out of statehouses,” [Tumlin] said. “The era of anti-immigrant state policies has subsided.”

Instead of trying to imitate Alabama’s HB 56 and Arizona’s SB 1070, states are embracing measures to help integrate immigrants into their communities, such as allowing state residents to apply for driver’s licenses regardless of immigration status. The lawsuits over HB 56 and the embarrassment it brought to Alabama served as a warning to other states against passing similar laws, but the settlements also should be a reminder for Congress to take action on comprehensive immigration reform. Alabama lawmakers said they passed HB 56 because federal officials weren’t acting on immigration. Now it’s up to members of Congress to improve the nation’s immigration system for every state so that individual states do not have to take piecemeal action.

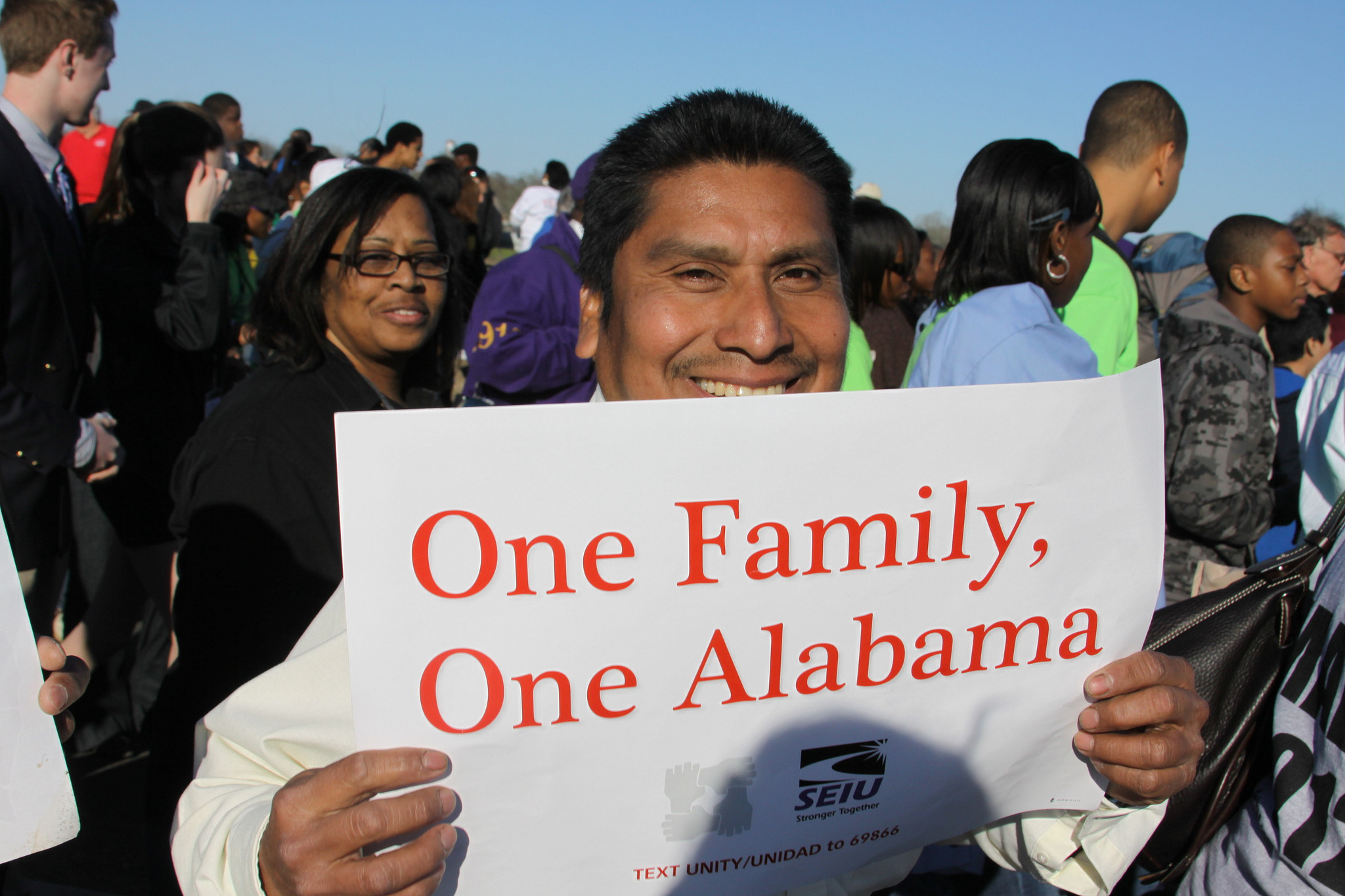

Photo courtesy of SEIU.

FILED UNDER: ACLU, Alabama, featured, HB 56, National Immigration Law Center, Southern Poverty Law Center