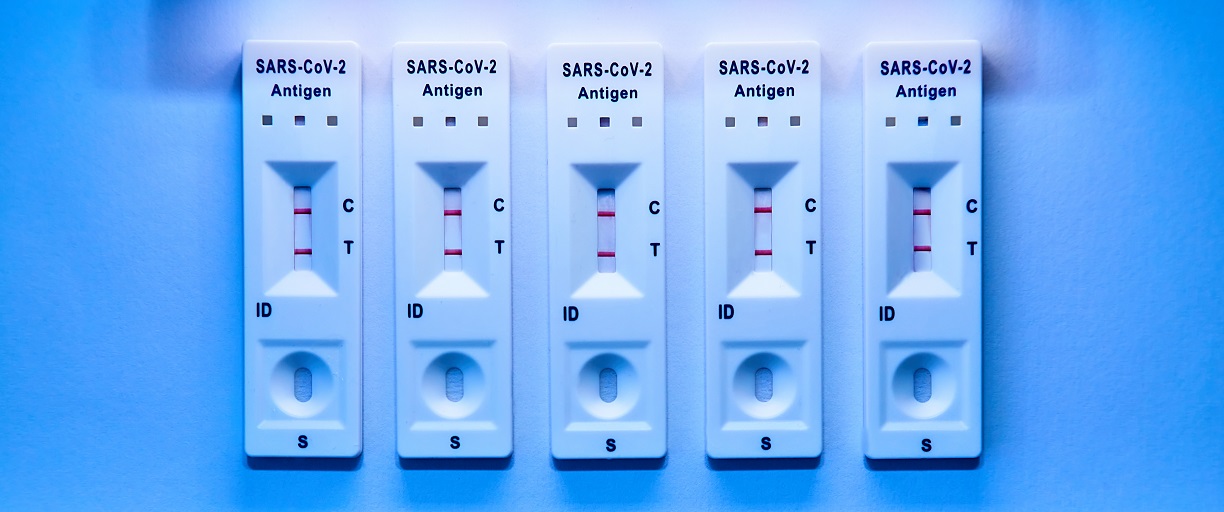

The Omicron variant has spread through immigration detention like wildfire, with a record 14% of people in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody testing positive for COVID-19 as of February 1, 2022. That day, over 3,000 people in ICE custody had active cases, a 1,000% increase from one month prior.

Despite the severity of the situation, detention centers continue to violate ICE policy intended to slow the spread of the virus. On February 11, advocates and six people currently or recently detained at the Denver Contract Detention Facility in Aurora, Colorado filed a complaint calling for an investigation into such violations.

The complaint addresses the three Department of Homeland Security (DHS) oversight agencies: the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, the Office of the Inspector General, and the Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman. It alleges that ICE and its contractor—the private prison company GEO Group—have violated ICE guidance and federal law during a recent COVID-19 outbreak at Aurora. As evidence, the complaint includes a signed declaration from each of the six individual complainants: Ramiro,* Santiago,* Leticia,* Musa,* Afuom,* and Camilo.*

First, the complaint alleges that the detention center is violating ICE’s COVID-19 guidance. It describes how ICE and GEO have failed to protect the health of high-risk people; provide sufficient testing, vaccines, cleaning supplies, and access to services; and ensure proper masking. For example, Camilo* reports that he never received a COVID-19 test even though he was exposed and symptomatic. He was not offered a vaccine until he had been at the detention center for four months and can only access one mask at a time—sometimes only once a week.

The complaint also alleges that ICE and GEO are violating ICE’s detention standards by failing to provide medical care to people sick with COVID-19.

Afuom* states, “I felt very sick and was having trouble breathing. I was hot and shaking. I asked for emergency medical but was told to submit a [written request]. In my weakened condition, all I could do was lie down in bed. Since this time, I have continued to struggle with breathing. I wake up in the middle of the night unable to catch my breath. I have not received medical treatment for my difficulty breathing.”

Another detention standard protects people in ICE custody from retaliation, but several of the complaints express a fear of speaking out about what is happening at the detention center. Camilo* reports that a member of the medical staff said, “They were going to move 13 people who tested positive to another dorm,” and instructed Camilo and others to “not talk to our attorneys or the news about this.”

Finally, the complaint alleges that ICE and GEO have violated federal disability law by failing to accommodate people detained at Aurora who have physical and mental disabilities. Musa,* who suffers from “post-traumatic stress disorder; major depressive disorder; recurrent, severe, unspecific psychosis; unspecified anxiety disorder; and blackouts,” states:

“When I woke up on the ninth day, I was confused and scared. I had had a blackout the night before. When I have blackouts, I am not aware of anything that is happening and I become gullible. You could put my hands in a fire, but I wouldn’t be able to react to it. I had a very severe mental breakdown on the ninth day, so I kicked the door a couple of times to get the attention of the officer and I told him he ha[d] to take me to medical…I think I was having a panic attack.”

Solitary confinement is harmful to anyone, but this treatment is especially inappropriate for someone with serious mental health conditions.

These recent examples are a continuation of ICE’s failure to implement basic public health measures throughout the entire pandemic. Federal courts, whistleblowers, oversight agencies, and internal emails have repeatedly shown ICE’s neglect has led to the spread of COVID-19 in detention.

And while the pandemic has further emphasized the dangers of immigration detention, policy violations were common long before the pandemic. For example, the American Immigration Council and the American Immigration Lawyers Association filed complaints in 2018 and 2019 regarding ICE and GEO’s failure to provide medical care at Aurora.

Given these failures, release is the most effective way to protect the health, safety, and due process of people fighting their immigration cases. It also protects public health in surrounding communities as outbreaks often spread beyond the walls of detention centers. ICE should release Ramiro,* Santiago,* Leticia,* Musa,* Afuom,* Camilo* and other people in its custody so that they can continue their immigration cases from their communities.

* denotes use of a pseudonym to protect the person’s identity.

FILED UNDER: covid-19