Use-of-force by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) personnel in Fiscal Year (FY) 2015 declined more than 26 percent compared with the previous year, according to statistics released last week by CBP. During FY 2015, which ended in September of last year, CBP reported 756 uses-of-force, down from the 1,037 in FY 2014 and 1,215 in FY 2013. Border agents used their firearms 28 times in FY 2015, one less than FY 2014, and so far seven times this year.

CBP’s recent announcement on uses-of-force was a follow up to information released in October of 2015 to include data from this current year. However, this announcement was met with skepticism by many.

First, according to the Los Angeles Times, “the official tally omitted at least one fatal shooting in El Paso, calling into question its accuracy and highlighting the need for more detailed reporting, civil rights advocates said.” That incident which occurred on February 4, 2016 was not initially reported by CBP but has since been updated after the Times contacted the agency.

Second, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has pointed out CBP’s use of force definition is too narrow. CBP noted in its announcement, “For reporting purposes, CBP categorizes use-of-force as either “firearm,” or “less-lethal device” or “other less lethal force.” But, according to Terri Burke, executive director of ACLU Texas, “CBP’s release today celebrates a decrease in use-of-force incidents based on incomplete statistics that exclude many uses-of-force as defined by the Department of Justice. Because CBP has no proper definition of a reportable use of force, there’s no way to identify the prevalence of incidents accurately.” As Chris Rickerd of the ACLU explained, “State and local police, for example, would typically report drawing their firearm as a use of force to compel compliance, Border Patrol seemingly doesn’t have anything like that.”

Lastly, CBP did not disclose how many of these use-of-force incidents resulted in serious injury or death and whether these use-of-force incidents are only self-reported by the agents and officers themselves or whether these numbers are based on an external investigation or an audit conducted by CBP. Most importantly, the report does not provide information on whether use-of-force was justified in the incidents reported or whether such incidents were followed by any investigations. It is also unclear whether CBP held agents and officers accountable where they were found to have used excessive force in situations where such use could have been avoided.

As Chris Rickerd, from ACLU summed up,

“The large, steady number of ‘less lethal’ force incidents demands more context: Why hasn’t the agency’s new emphasis on de-escalation had a larger effect and what disciplinary consequences have resulted from force incidents that violate policy? Finally, the Border Patrol’s propensity to frequently use force underscores our disappointment at its slow pace of accountability reforms. Body-worn cameras within a strong policy framework are badly overdue and an independent law-enforcement panel’s June 2015 use-of-force recommendations must be implemented immediately.”

Most agree that CBP should use force sparingly, and while many are encouraged that CBP is publicly releasing more statistics, without additional context and information, it is difficult to assess what these statistics actually represent or mean.

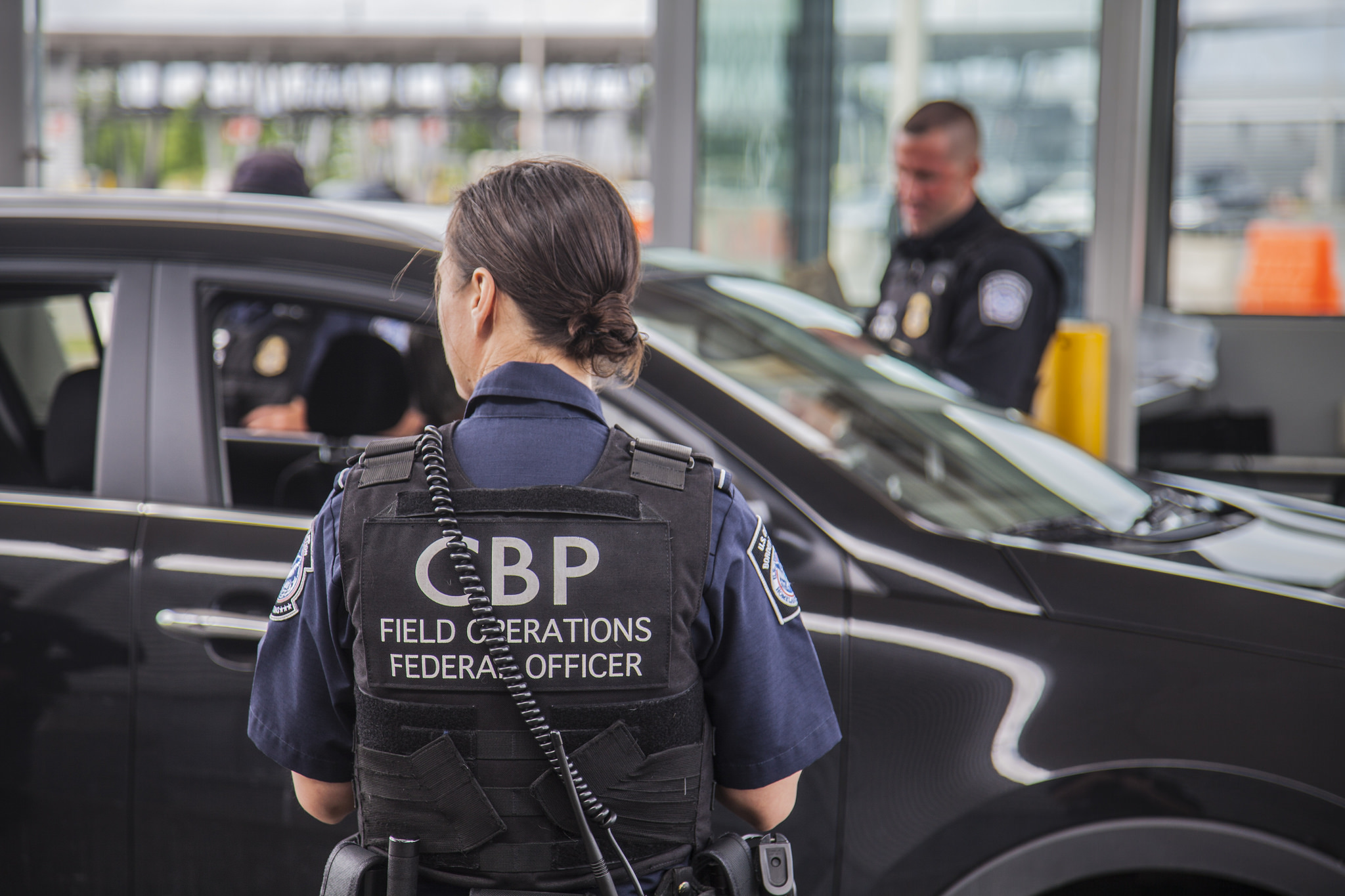

Photo Courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

FILED UNDER: ACLU, border patrol, Customs and Border Protection, featured