The Washington Post published an editorial last week that missed the mark on whether the President has the authority to limit deportations of undocumented immigrants, concluding President Obama would be “tearing up the Constitution” by doing so. The New York Times editorial board followed up Sunday with their more accurate assessment that it “would be a rational and entirely lawful exercise of discretion” for Obama to use his authority focus on high-priority immigration targets.

The Washington Post published an editorial last week that missed the mark on whether the President has the authority to limit deportations of undocumented immigrants, concluding President Obama would be “tearing up the Constitution” by doing so. The New York Times editorial board followed up Sunday with their more accurate assessment that it “would be a rational and entirely lawful exercise of discretion” for Obama to use his authority focus on high-priority immigration targets.

The truth is, the President has the responsibility, as well as the authority, to regulate the enforcement of immigration law, a task that has become far more difficult in light of Congress’ failure to pass immigration reform. Given this failure, the president must use the executive authority available to him to create a more fair and transparent process for determining who should be deported and who should be allowed to remain in the United States temporarily.

Hiroshi Motomura, a legal scholar and professor at the UCLA School of Law school, has described in detail the President’s legal authority to exercise this power, noting in a new book that the immigration scheme in the United States has always been one of “selective enforcement,” in which we acknowledge, either directly or indirectly, that not everyone in the country unlawfully will be deported. In recent years, the Obama administration has moved from the informal acknowledgment of that truth to a more targeted process, moving from merely articulating enforcement priorities to actually designating factors that should, as a general rule, preclude deportation. Critical to this process are two points—both of which ensure that the Constitution remains undamaged.

First, designating a more regular process—such as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program for undocumented youth who arrived in the U.S. as children—sets a broad parameter of eligibility, but it does not dictate that an individual will necessarily be allowed to remain in the U.S. Case-by-case adjudications require individual exercises of prosecutorial discretion. This individualized determination ensures that the government continues to act within its inherent role of enforcer of the laws, a role that by its nature also includes the discretion to decline to prosecute in individual cases. DACA, and any potential expansion of it, merely ensure that this individualized assessment is conducted in a formal and more accountable manner.

Second, the president cannot grant permanent legal status. That is the role of Congress. No one who currently has DACA will become a permanent resident or U.S. citizen based on that temporary reprieve from deportation. Instead, DACA provides young people the breathing room to pursue education, work, and have a more predictable life, albeit within two-year increments. It also provides Congress the breathing room, if it will take it, to structure a legalization program that would provide closure to the endless debate over undocumented immigrants in this country.

As long as the president is transparent and rational in the criteria established, and as long as the underlying decision is individualized, a broader program has the potential to refocus our energies on genuine threats to our nation, expand the economic and social contributions of individuals who are already embedded in our communities, and create the space for more legislative action.

There is a difference between authority and policy. Whether the president has the authority to exercise discretion in this way is undisputed. Whether it is good policy is the real debate. There, the evidence is clear. In the absence of Congressional action, creating a more predictable and rational approach to regulating undocumented immigration is the best option available.

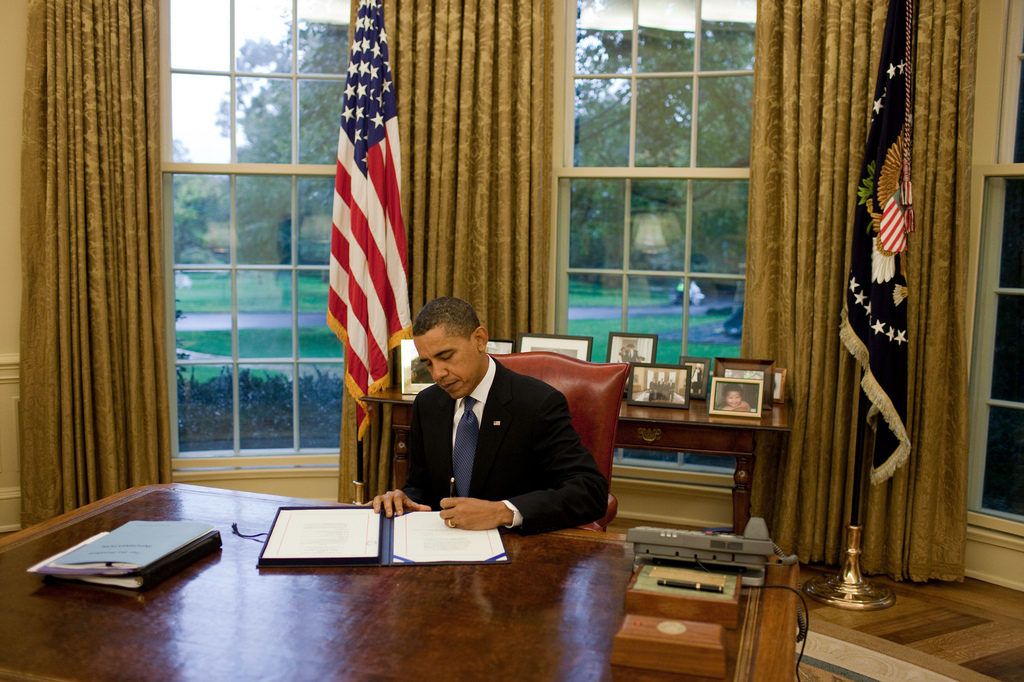

Photo by Stefaan.

FILED UNDER: DACA, Executive Branch, featured, Hiroshi Motomura, President Obama, prosecutorial discretion, undocumented immigration