Along with campaign ads and ballot initiatives, the November elections inevitably bring allegations that non-citizens are turning out in droves to skew elections. Despite repeated investigations over the years finding no indication that systematic vote fraud by non-citizens occurs, some voters will have to navigate cumbersome voter identification laws designed to address a non-existent problem.

Supporters of these laws like to pretend that non-citizens are crowding into voting booths and illegally changing the outcome of critical elections. But the reality is that voter ID laws have little to do with the exceedingly rare occurrence of illegal voting by immigrants, or any other kind of voter fraud. These are laws designed to disenfranchise racial and ethnic minorities, the poor, and other social groups that might be inclined to vote. In other words, voter ID laws are meant to limit democracy, not protect it.

Despite the evidence to the contrary, a recent study claims that about 6 percent of non-citizens voted in 2008 and 2 percent voted in 2010. The authors, Jesse Richman and David Earnest, say their analysis of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) data shows that enough non-citizens voted “to plausibly account for Democratic victories in a few close elections.” But others point out the methodological flaws in their research. As Michael Tesler explains in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, the 2008 and 2010 CCES data came from “opt-in Internet samples constructed by the polling firm YouGov to be nationally representative of the adult citizen population.” These kinds of self-selective surveys can be suspect in themselves, but the reporting around citizenship status appears especially fraught with error. Tesler writes that over the course of several CCES surveys, the same individuals identified themselves initially as citizens and in a subsequent survey as non-citizens, putting into question the validity or meaning of the data Tesler argues it would be “tenuous at best” to draw assumptions about non-citizens who responded to a survey about American politics, especially when many of those respondents could have simply clicked the wrong box.

The truth is that suspected cases of voter fraud are few and far between. Attempts in 2012 to find non-citizens who had illegally registered to vote turned up little, as the Associated Press reported. In Colorado, an initial list of 11,805 suspected non-citizens on the voter rolls shrunk to 141, or .004 percent of the state’s 3.5 million voters. Likewise, in Florida, a list of 180,000 suspected noncitizens on the rolls has shrunk to 207 out of the state’s 11.4 million registered voters. Some of the individuals in question did not even know they were registered to vote.

Headlines in conservative outlets proclaimed that the analysis of the CCES data confirmed the worst fears about rampant voter fraud, but it appears that some critical flaws in the data mean that there is really no new story here. Instead, the idea that non-citizens are swaying elections remains a convenient myth designed to stir up fear and restrict access to voting.

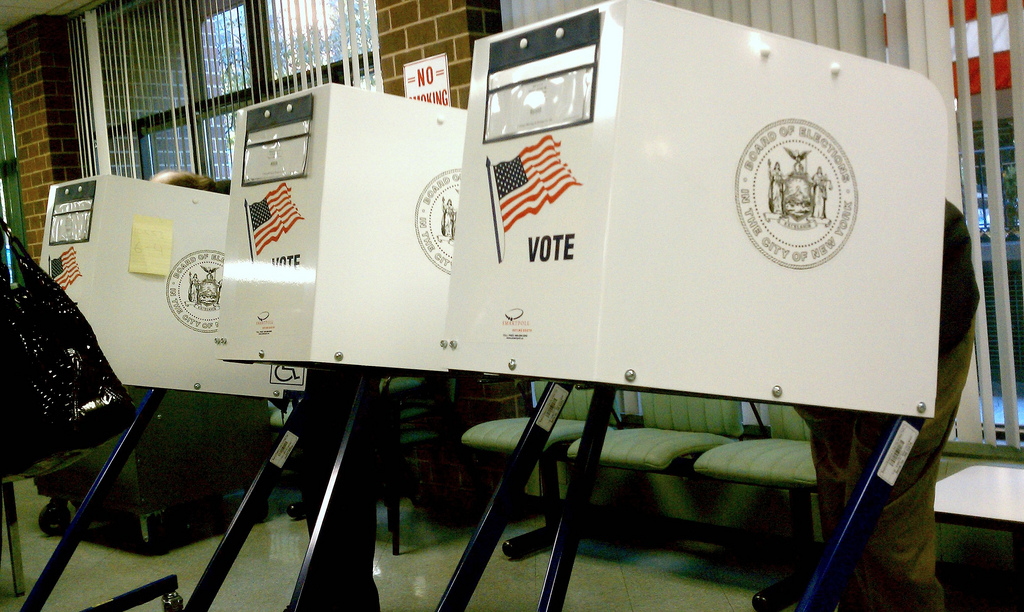

Photo by Charles16e.

FILED UNDER: Election 2014, featured, Immigration 101, Voting