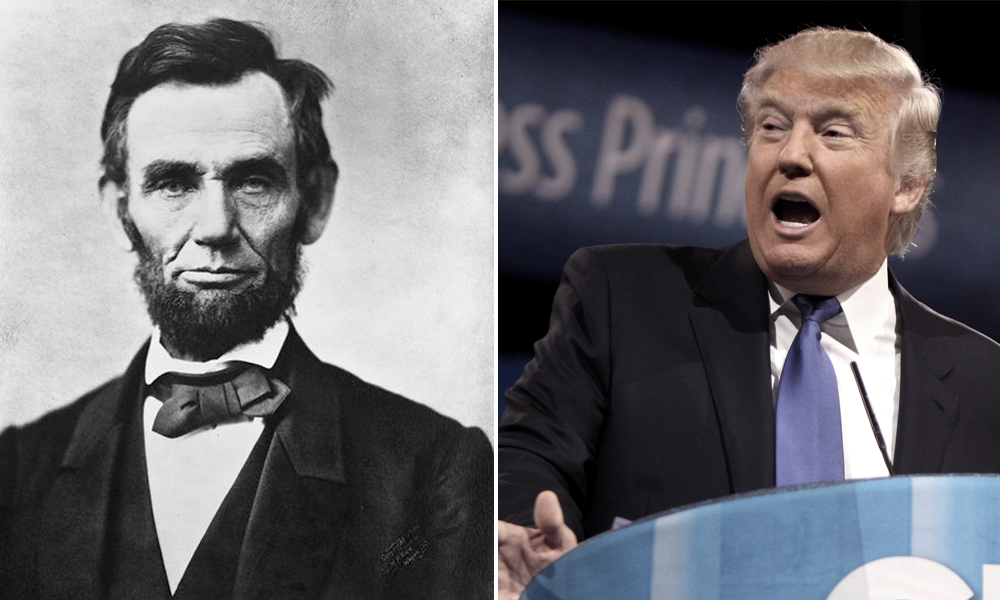

Although much has been written about how the party of Abraham Lincoln became the party of Donald Trump, one additional area where these two men parted ways is immigration.

The world of today is different from the world in which Abraham Lincoln lived or could have imagined. And I know full well the perils of presentism—the often misguided notion that you can judge people and events of the past by the world in which you currently live. Nevertheless, the language and ideas of the current Republican Party platform are “punitive, inflammatory, and impractical” compared to the rhetoric of Lincoln’s era. Assuredly, Lincoln would not understand the underlying sentiment behind this language and these ideas. It wasn’t in his nature to be punitive or exclusionary.

Still, even if you accept the argument that the world is dangerously different from Lincoln’s time, long before he spoke about the evils of slavery, he consistently articulated an economic philosophy that relied heavily upon immigrant labor. From his earliest speeches on, Lincoln saw immigrants as the famers, merchants, and builders who would contribute mightily to the economic future of the United States.

Lincoln assisted in the writing of the 1864 platform for National Union Party (or the Republican Party as it called itself then) in its convention at Baltimore. He insisted that the following sentence be included in their platform stating: “That foreign immigration, which in the past has added so much to the wealth, development of resources and increase of power to this nation, the asylum of the oppressed of all nations, should be fostered and encouraged by a liberal and just policy.”

Consequently, Lincoln pushed for the first, last, and only law in American history to encourage immigration—one that is often overlooked.

Lincoln’s Act to Encourage Immigration was fittingly passed on July 4, 1864. “A liberal disposition towards this great national policy is manifested by most of the European States,” wrote Lincoln, “and ought to be reciprocated on our part by giving immigrants effective national protection. I regard our emigrants as one of the principal replenishing streams which are appointed by Providence to repair the ravages of internal war, and its wastes of national strength and health.”

Congress responded to Lincoln’s request and America opened up its doors to immigrants if only for a short time.

That is what Lincoln and the Republicans of 1864 stood for. One hundred and fifty-two years hence notwithstanding, this is a significant difference in tone, demeanor, and philosophy. That fact is inescapable and, while Lincoln himself like many nineteenth-century western Americans occasionally spoke in derogatory terms about some ethnic groups, his actions often belied those harsh words with kind actions. Pandering political rhetoric and humane action need not always be inconsistent and Lincoln demonstrated that. Perhaps it is time today’s politicians learned that lesson as well.

By Jason H. Silverman, Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History at Winthrop University and author of the recently published Lincoln and the Immigrant.

Photo Courtesy of Gage Skidmore and Believe Creative.

FILED UNDER: Donald Trump, Election 2016, featured