The highest courts of Florida and California are considering a legal question of great importance to many DREAMers: whether the lack of valid immigration status prevents states from issuing law licenses to applicants who are otherwise qualified to become attorneys. To some, the answer may seem obvious—that immigrants should not be permitted to practice law in a country where their presence violates the law. But as with most issues concerning immigration, the answer is more complex than may initially appear.

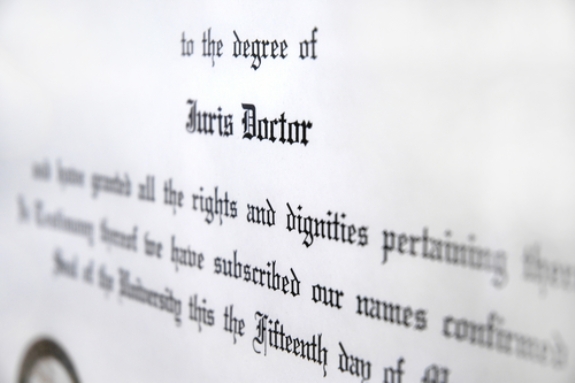

The cases involve two immigrants—Sergio Garcia in California, and Jose Godinez-Samperio in Florida—who graduated from law school and passed the bar exam, but have yet to receive their law licenses due to a lack of immigration status. Although each was ultimately found eligible by the state’s bar committees, their cases remain pending at the highest courts of their state, which have final power over whether prospective attorneys may practice law. The cases have drawn outside briefs from a wide range of parties, including former presidents of the American Bar Association, arguing that immigration status should not control fitness to practice law.

Although the idea of an attorney without legal status appearing in court might seem counterintuitive to some, the briefs put forward a number of reasons in support of the idea. For one thing, simply because an individual currently lacks immigration status does not mean he is not attempting to obtain—and may one day obtain—lawful permanent residence. According to media accounts, for example, Garica’s green card application has been pending for well over a decade. For another, even immigrants who are unlawfully in the country may receive employment authorization in certain circumstances, such as Godinez-Samperio, who could receive a work permit under the administration’s new “deferred action” policy (Garcia is too old to qualify).

For its part, the Obama administration submitted a brief in the California case opposing Garcia’s request for a law license. According to the Justice Department, a provision of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 prohibits states from giving “professional licenses” to immigrants who lack permission to be in the country. The administration also said that even if an undocumented applicant received a license, he would not necessarily be entitled to work in the country, even as a solo practitioner. Importantly, however, the administration didn’t foreclose the possibility that Garcia could practice law in the future, because the 1996 law makes an exception in states that pass legislation allowing undocumented immigrants to receive professional licenses.

Putting aside whether undocumented residents who pass the bar exam should be permitted to practice law, the larger question remains why anyone would want young people who have succeeded in getting an education deported in the first place. Some politicians love to say that visiting students who obtain advanced degrees in the United States should have a green card stapled to their diploma. Under this logic, if immigrants with advanced degrees are inherently worthy of permanent residence, why should it matter whether one who finishes law school and passes the bar exam has valid immigration status, especially if brought to the country as a child? Regardless of how they got to this country, their degrees have the same value. Even a lawyer would have a hard time defending that distinction.

FILED UNDER: Department of Justice, DREAM Act, Driver's Licenses, Executive Branch, Immigration Law, undocumented immigration