The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began collecting DNA from people held at the border earlier this month. This is part of a pilot program that DHS plans to expand nationwide. The program is currently operating at the port of entry in Eagle Pass, Texas and within the Border Patrol’s Detroit Sector.

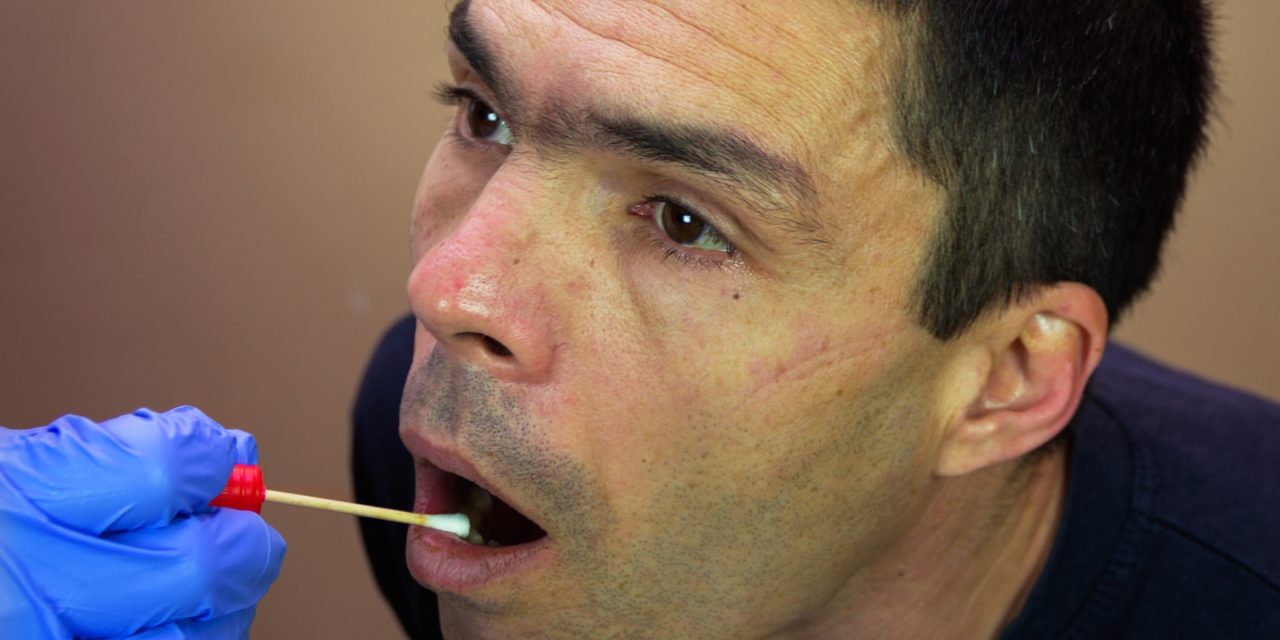

When fully implemented, the program would collect the DNA of nearly all people arrested by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) over the age of 14. This will include U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. People who refuse to comply could face prosecution.

The privacy implications of this new program are enormous, while the benefits for law enforcement are negligible.

The Department of Justice estimated that over 740,000 people would have been subject to this program over the last year. ICE alone had approximately 41,000 people in its custody as of January 11.

Proponents of the program argue it can help link immigrants to prior crimes and reveal the immigration history of people who misrepresent their identity at the border. But DHS has acknowledged that it won’t be able to process the DNA fast enough for it to be useful in ongoing criminal investigations.

Opponents fear this type of mass collection of genetic information could alter the fundamental and stated purpose of DNA collection. Instead of aiding in criminal investigations, it would become a tool of mass population surveillance.

Congress passed the DNA Fingerprint Act in 2005. The act gave the Attorney General the authority to require collection of DNA samples from people arrested or detained by the federal government.

Since that time, the government has avoided extending DNA collection to most people held in immigration custody. Officials reasoned the practice was unfeasible and too costly.

As Brian Hastings, chief of the Border Patrol’s law enforcement directorate, stated in a recent deposition:

“Even once such policies and procedures were put in place, Border Patrol Agents are not currently trained on DNA collection measures, health and safety precautions, or the appropriate handling of DNA samples for processing.”

The Border Patrol has approximately 20,000 agents on staff. The resources needed to train that many agents to properly collect and handle DNA samples would be astronomical. The 8,000 ICE officers that work with detainees would also require training. DHS would also need to consider the patchwork of contractors that run many of our country’s detention facilities.

The Department of Justice estimates the program will cost DHS nearly $14 million over its first three years. That money could instead be used to improve the horrendous conditions for the people held in CBP custody.

This is why former DHS Secretary Napolitano decided in 2010 that categorical DNA collection from people held in immigration custody was not feasible. Since then, only people subjected to DNA collection were those detained while facing criminal charges.

The Trump administration now claims that the associated costs and training have changed so much that it must be pursued en masse, despite the fact that DHS already collects other biometric information such as photographs and fingerprints.

Once collected, the genetic information will go to the FBI and be added to their Combined DNA Index System. The index will store the information indefinitely, creating a permanent law enforcement record for many people who have not been accused or convicted of a crime.

Our DNA profile reveals an extraordinary amount of information about us and our families. People should only be compelled to provide this information under the most serious circumstances.

Forcing people to submit their DNA under threat of prosecution is expensive and unnecessarily invasive. It also gives the federal government the ability to surveil hundreds of thousands of new people every year—predominantly people of color from Mexico and Central America.

FILED UNDER: Customs and Border Protection, Department of Homeland Security